Leveraging school meals and the school environment to accelerate efforts toward anemia reduction

Photo: Ron Lach/Pexels

The world is home to 1.8 billion adolescents, of which 90% live in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). (1) Anemia remains a significant public health concern for this sizable yet overlooked population. (2) Indeed, adolescents are particularly susceptible to micronutrient deficiencies, referred to as hidden hunger, with iron deficiency anemia being one of the leading causes of disability-affected life years (DALY) lost for girls and boys aged 10-14 and girls aged 15-19. (3) The demand for iron rises during these crucial years of growth and development, thereby increasing the risk of iron deficiency anemia.

Despite efforts to increase iron intake, progress on global anemia reduction has been disappointingly slow. (4) There is a substantial body of evidence highlighting the positive impacts of school feeding on adolescents’ health and well-being. (5) Considering this trend, there remains a glaring need for alternative approaches to fill the iron gap.

The 5th International Congress Hidden Hunger, whose theme was “Improving Food and Nutrition Security through School Feeding," served as an excellent platform to engage with multi-disciplinary researchers, health practitioners and NGOs to share successful strategies and to develop actionable plans to enhance school feeding programs as a vital tool in the battle against malnutrition, specifically anemia.

The main aim of the conference was to explore how to make school meals accessible and affordable to all children and adolescents. School meals have far-reaching benefits, from alleviating short-term hunger to filling critical micronutrient deficiencies through health and nutrition education and dietary diversity. (6) Yet, providing school meals alone is insufficient to address the complex etiology of iron deficiency anemia among adolescents. To truly make headway, we need a multi-faceted approach that tackles both the direct and underlying causes of anemia. (7)

[caption id="attachment_48901" align="alignnone" width="819"]

Sight and Life’s session at Hidden Hunger Congress. Photo: Rachel Natali/Sight and Life[/caption]

Sight and Life’s session at Hidden Hunger Congress. Photo: Rachel Natali/Sight and Life[/caption]

Building on this approach, Sight and Life hosted a session at the conference on the full potential of the school environment in addressing iron deficiency anemia in adolescents in LMICs. We discussed existing gaps in micronutrient provision through school meals and presented solutions to address these gaps, such as fortified foods or fermented foods, dietary diversification, and supplementation. The session showcased an inclusive business model, that is working to fill a nutrition gap for school-going adolescents in Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia and a few other LMICs by making probiotic yogurt widely available while supporting local production.

While school meals are a vital source of nutrition for adolescents, they cannot do the job alone – especially when it comes to meeting essential nutrient needs for optimal health, including iron. (7) A nutritious meal becomes even more effective when paired with additional context-specific health and well-being interventions. (2) By leveraging the entire school environment, we can deliver an integrated package of interventions that address the multiple health and nutrition challenges adolescents face. Apart from meals, such a holistic intervention package could include:

- Incorporating phytase-rich foods in school meals can make it easier for the body to absorb and utilize iron. (8)

- Malaria treatment can mitigate anemia caused by chronic infections. (9)

- Programs focusing on water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) can reduce the incidence of parasitic infections that exacerbate anemia while deworming initiatives further support this by eliminating intestinal parasites that cause blood loss and hinder nutrient absorption. (7)

- Daily iron and folic acid supplementation (WIFAS) can also boost iron levels. (7)

- Sexual and reproductive health education, including menstrual health management, can equip adolescent girls with the knowledge and resources to manage menstruation, a life stage with increased iron requirements. (7)

Through diverse partnerships involving academia, policymakers and local organizations, this session sought to accelerate efforts toward anemia reduction with a whole-school approach, complemented by both iron-specific and iron-sensitive interventions.

Finally, school meal programs are highly impacted by meal consumption habits, including breakfast habits, a commonly skipped meal by adolescents worldwide. (10) The event showcased a poster describing Sight and Life’s ongoing systematic review evaluating the association of breakfast skipping with anthropometric and nutritional outcomes in adolescents residing in LMICs.

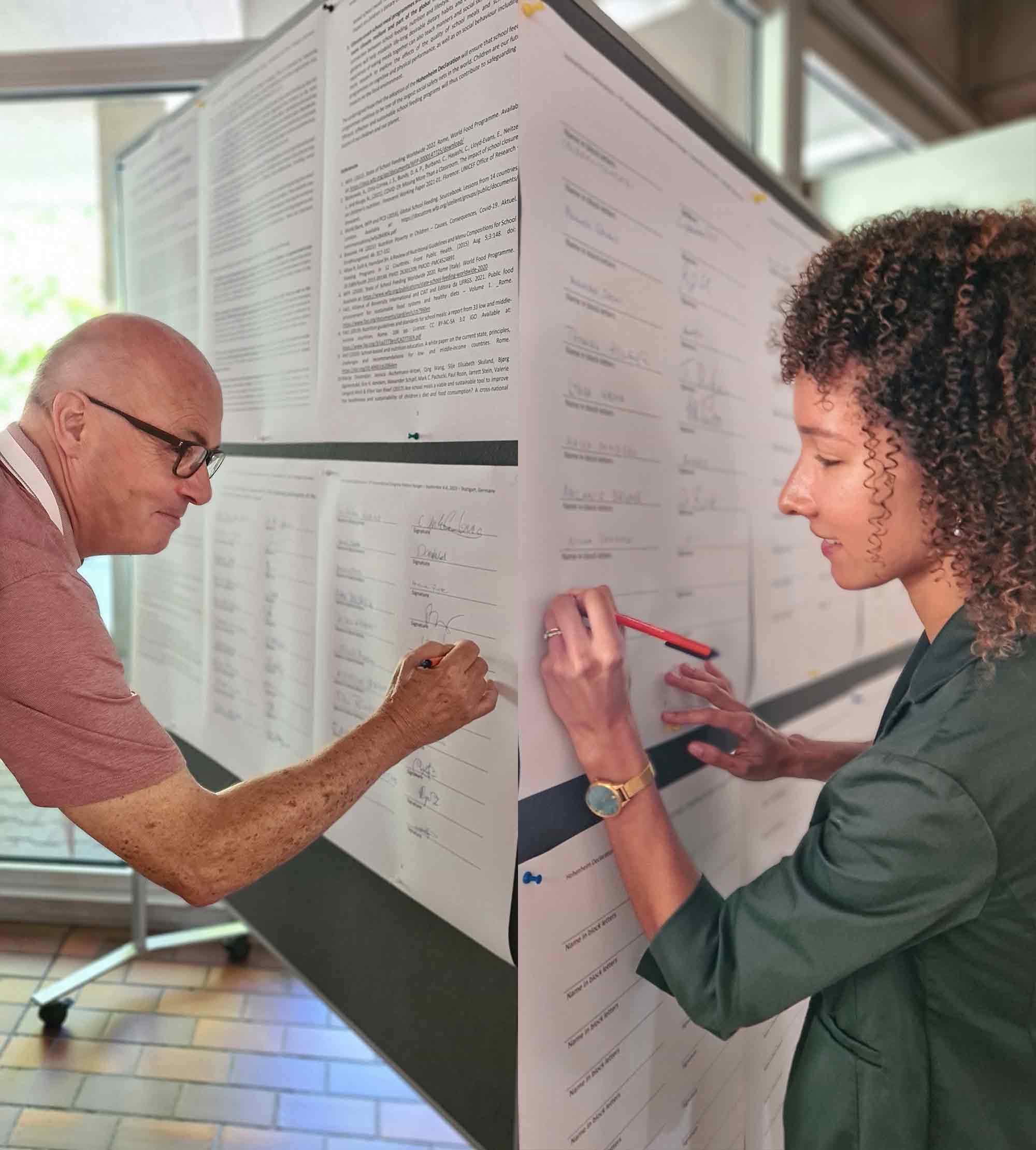

At the culmination of the Congress, attendees and the Congress Scientific Advisory Board put forth the Hohenheim Declaration. Sight and Life stands in full agreement with the five declarations set forth and believes prioritizing school feeding programs is imperative to realizing food security and nutrition.

[caption id="attachment_48900" align="alignnone" width="778"] Signing of Hohenheim Declaration. Photos: Rachel Natali/Sight and Life[/caption]

Signing of Hohenheim Declaration. Photos: Rachel Natali/Sight and Life[/caption]

We thank the event speakers for participating and sharing their knowledge in our effort to close the micronutrient gap through the school platform. We are grateful to the Hidden Hunger Congress organizers for their excellent coordination and for creating a space to unite those passionate about sustaining and increasing the reach of the world’s most extensive social safety net.

[caption id="attachment_48902" align="alignnone" width="804"] Session speakers and moderator (L to R: Kesso Gabrielle van Zutphen-Küffer, Sight and Life; Vanessa Garcia-Larsen, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Jordie Fischer, Sight and Life; Lucy Murage, Nutrition International; and Wilbert Sybesma, Microbiome Solutions and Yoba4Life) Photo: Rachel Natali/Sight and Life[/caption]

Session speakers and moderator (L to R: Kesso Gabrielle van Zutphen-Küffer, Sight and Life; Vanessa Garcia-Larsen, The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; Jordie Fischer, Sight and Life; Lucy Murage, Nutrition International; and Wilbert Sybesma, Microbiome Solutions and Yoba4Life) Photo: Rachel Natali/Sight and Life[/caption]

Schools provide an avenue for a wide range of collaborations, where both the education and health sectors are invested in the 𝘄𝗲𝗹𝗹𝗯𝗲𝗶𝗻𝗴 𝗼𝗳 𝗮𝗱𝗼𝗹𝗲𝘀𝗰𝗲𝗻𝘁𝘀 and should therefore be considered a ‘partnership' rather than just a delivery 'platform.'” - Lucy Murage

Featured photo courtesy of Ron Lach/Pexels

References:

1. United Nations. World Population Prospects 2017. New York: UN Department for Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA), Population Division; 2017.

2. Baltag V, Sidaner E, Bundy D, Guthold R, Nwachukwu C, Engesveen K, et al. Realising the potential of schools to improve adolescent nutrition. BMJ. 2022 Oct 27;379:e067678.

3. World Health Organization. Global Health Estimates 2019: Causes of DALYs and mortality by cause, age, sex, by country and by region, 2000–2019. Geneva: WHO; 2019 [cited 2023 Sep 26]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/global-health-estimates-leading-causes-of-dalys

4. United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Undernourished and Overlooked: A Global Nutrition Crisis in Adolescent Girls and Women. New York: UNICEF; 2022. (UNICEF Child Nutrition Report Series). Available from: https://www.unicef.org/reports/undernourished-overlooked-nutrition-crisis

5. Wang D, Shinde S, Young T, Fawzi WW. Impacts of school feeding on educational and health outcomes of school-age children and adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04051.

6. World Food Programme (WFP). State of School Feeding Worldwide 2022. Rome; 2022. Available from: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000147725/download/?_ga=2.237309448.984506589.1693917653-1504288076.1693917653

7. World Health Organization. Accelerating anaemia reduction: a comprehensive framework for action. Geneva: WHO; 2023. Available from: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/367661

8. Troesch B, Jing H, Laillou A, Fowler A. Absorption studies show that phytase from Aspergillus niger significantly increases iron and zinc bioavailability from phytate-rich foods. Food Nutr Bull. 2013 Jun;34(2 Suppl):S90-101.

9. WHO. Global anaemia reduction efforts among women of reproductive age: impact, achievement of targets and the way forward for optimizing efforts. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240012202

10. Keats EC, Rappaport AI, Shah S, Oh C, Jain R, Bhutta ZA. The Dietary Intake and Practices of Adolescent Girls in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review. Nutrients. 2018 Dec 14;10(12):1978.

Read next

Discover more

News & announcements

Find out what is new at Sight and Life

Multimedia

Explore our videos, podcasts, and infographics