Diverse Proteins: The nutritionists perspective

The world’s population is growing, and for many, the question of how we ensure an adequate food supply for all while sustaining our planet and natural resources is a crucial one. Fundamental to addressing the current global nutrition crisis is to deliver food that can guarantee delivery of adequate nutrients to people affected by all forms of malnutrition and the population as a whole. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), sustainable diets have a low environmental impact while contributing to food and nutrition security for our present and future generations. In other words, sustainable diets should respect and protect ecosystems and biodiversity next to being culturally acceptable, affordable, accessible, safe and healthy [1].

The food industry has shown the capability to rapidly adapt and innovate to meet the growing demand for more sustainable diets. This initiative is particularly reflected in the growing market for diverse proteins, which are increasingly becoming available to consumers, albeit in the Global North rather than Global South. This innovation responds to the globally growing demand for protein and could potentially alleviate some of the pressures on the food system. However, do these products meet the need for higher quality (i.e., more nutritious) food and help us move towards global food security?

Key messages

- The increasing demand for protein has resulted in rapid innovations led by the food industry in categories such as diverse proteins, of which the nutritional content can still improve.

- Currently, many alternative protein products are less than ideal substitutes considering they are high in salt, low in some key nutrients and often ultra-processed.

- Transparency regarding the nutritional content of diverse proteins is needed to inform consumers, enabling them to make informed choices.

- Policymakers, the food industry, consumers and nutritionists are called to dialogue to deliver nutritious and sustainable alternative protein products.

Diverse proteins – what are they?

Alternative protein sources encompass everything from algae to re-engineered plant-based legumes and a variety of meat substitutes. Think of lab-grown meat, plant-based meat, single-cell proteins from yeast or algae, and edible insects. The market share of diverse proteins has significantly increased in the past decade (read more in our blog post Alternative Protein: What’s the deal?), and a large variety of products are found in supermarkets throughout the Global North.

According to scientific literature, three factors have led to the increase of alternative protein consumption: animal welfare, environmental friendliness, and taste preferences [2]. Generally, the consumption of diverse proteins are found to be higher among women and the well-educated [2]. Women also tend to have a more positive attitude towards meat alternatives or diverse proteins than men due to perceptions of health and weight regulation. Overall, meat alternatives are perceived as healthier when compared to regular meat products. But besides the environmental and social marketing strategies (read more in our blog post Diverse Proteins: Speaking to consumers), what do we really know about alternative protein products’ nutritional value? How do diverse proteins fit in the transition towards healthy and sustainable diets for everyone, everywhere?

Beyond the headlines

Diverse proteins have the potential to disrupt the global food system in significant ways. Conscious of this movement, stakeholders’ interests are rapidly increasing. A complete understanding of the entire alternative protein landscape and its impact on public health and nutrition is required for both public and private actors to fully comprehend diverse proteins’ role within the global scenario. At Sight and Life, we value the importance of going beyond the persuasive environmental (Save the plant, Earth Day every day) and health (cholesterol-free, plant-based) claims that are currently associated with such products, and strive to understand the science and nutritional benefits of this emerging trend.

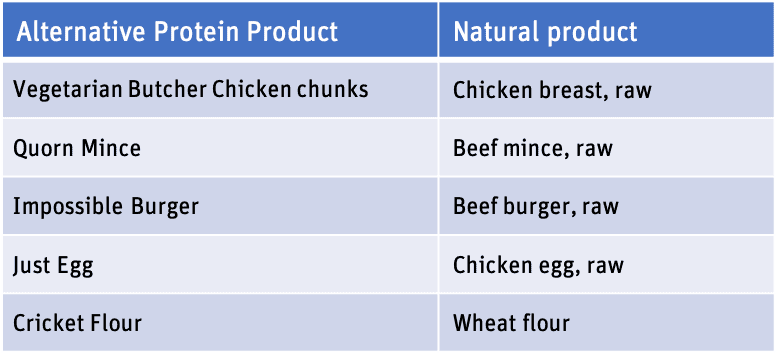

In this blog, we dive into the nutritional content of five popular alternative protein products consumed in the Global North and compare them to their ‘natural’ counterparts (Table 1).

Nutrient content

Most consumers quickly glance at the nutrient label and generally focus on the calories or energy content of the product. The energy content of the alternative protein products we reviewed was found to be roughly equal to that of their ‘natural’ counterpart. However, because the energy content of a product has very little to do with its nutritional content, a deeper nutritional investigation is warranted.

Sodium

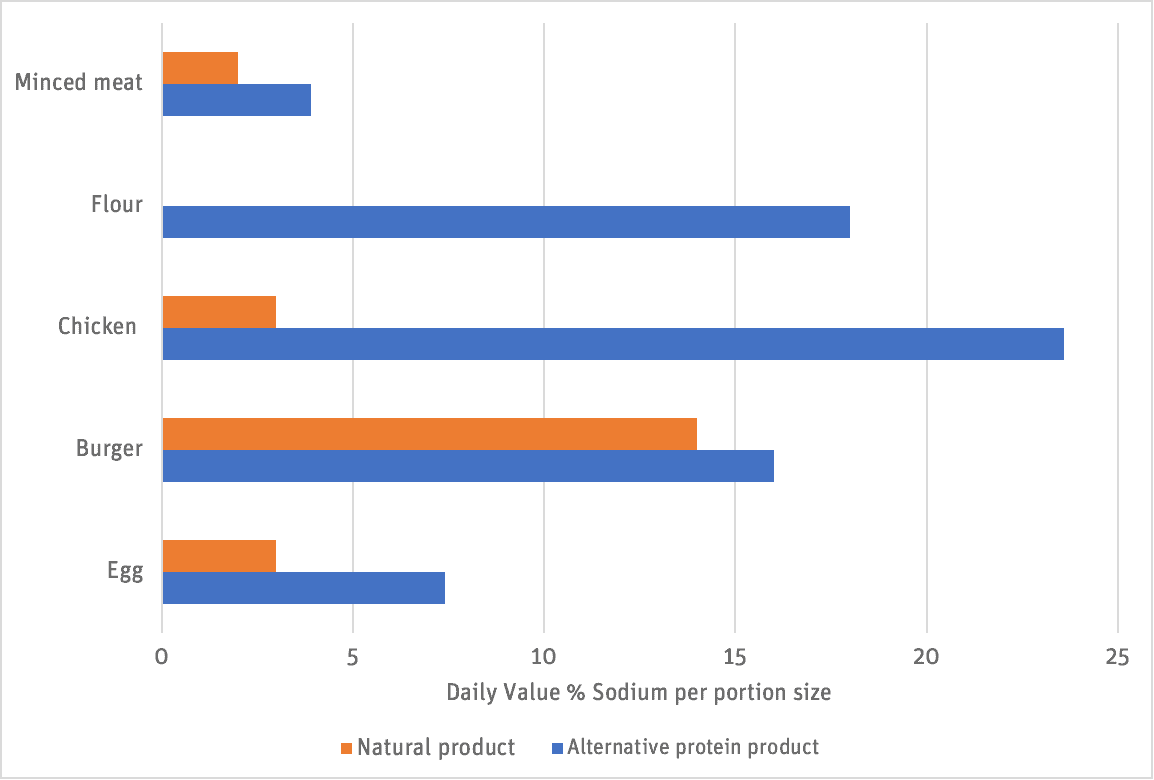

We took a look at the sodium (or salt) content – expressed in Daily Value % (DV) according to the U.S Food and Drugs Administration [3] – of alternative protein products compared with their natural counterparts. As illustrated in Figure 1, the same portion size of alternative protein and its natural counterpart contain varying DV% of sodium. In fact, the alternative protein products exceed the DV% of their natural equivalent. Remarkable is the sodium level found in the Chicken Chunks from The Vegetarian Butcher. One portion size of the vegetarian chicken chunks provides almost a quarter of your daily recommended salt intake whereas chicken is typically 4% DV. In other words, the consumption of one portion of the vegetarian Chicken Chunks leads to the intake of 1,36 grams of salt out of the 5 gram daily recommended by World Health Organization [4]. Scientific evidence shows that a high salt intake represents one of the major dietary risk factors for death worldwide [5] and is associated with an increased risk of high blood pressure, stroke, and cardiovascular diseases. Unfortunately, the findings from these five products are no exception. A study involving over 150 different plant-based products found only 4% of them to be low in salt [6].

Essential nutrients: Iron, zinc, and vitamin B12

Key nutrients such as iron, zinc, and vitamin B12 are absent in most of the alternative products except for the Impossible Burger, which has been fortified. In the vegetarian diet, these are known nutrients of concern [7;8]. This subject matter has also been observed in Curtain and Grafenauer’s study. The authors found that less than a quarter of plant-based products (24%) were fortified with vitamin B12, 20% with iron and only 18% with zinc [6]. While fortification of diverse proteins may be a potential solution, there is an urgent need to examine fortification in the context of bioavailability of nutrients in plant-based products – this continues to be an important yet unexplored area to date.

Labeling

Getting a clear overview of the actual nutritional content of some of the alternative protein products has proven to be rather difficult as the information provided online or on the nutritional label of the product was found to be limited. Data on energy (calories), macronutrients, and fiber are provided for all five alternative protein products reviewed. However, the nutrition labels of The Vegetarian Butcher Chicken Chunks and Quorn Mince lack nutritional information regarding key minerals (calcium, zinc) and vitamins (vitamin A, D, and B complex) (Figure 2). Not only did most products not contain iron and vitamin B12, but the lack of nutrient information on the label was concerning considering alternative protein products are often chosen as alternatives to meat products, which are a natural source of iron and B12.

Lack of key nutritional information on the label of alternative protein products does not guarantee a complete overview of their nutrient profile. How does this affect the nutrient intake of the consumer?

Processing and ingredient list

According to the latest FAO recommendations on ultra-processed food [9], it was found that four out of five analyzed alternative protein products were classified as such (Table 2). To assess whether alternative protein products can be defined as ultra-processed foods, the products’ ingredient lists were investigated. In particular, the presence of at least one specific class of ingredients or food substances in the food list was sufficient to define such product as an ultra-processed food. In most alternative protein products ingredient lists, we found thickeners, colors, flavors, additives, and emulsifiers, which are part of food classes characteristic of the ultra-processed food group identified by the FAO [9;10]. The cricket flour was the only alternative protein not classifiable as ultra-processed food. Furthermore, from the labeling investigation, we noticed that alternative protein products consisted of up to 21 different ingredients – except for the cricket flour, which is exclusively composed of dry crickets.

Conclusion

The growing demand for diverse proteins has resulted in rapid and impressive innovations from the food industry. It’s not yet perfect, but perhaps directing our efforts towards improved nutrition labeling, reformulation on nutrient content, and improved consumer awareness for these types of products will help us move towards a healthy and sustainable protein supply for all.

Consumer guidance and food industry regulations developed by policymakers could ease the transition to a plant-based diet in a healthy and sustainable manner. The EAT-Lancet report has also contributed to this debate by pushing for more sustainable (plant-focused) diets [11]. However, as a nutrition community, we should be cautious of the possible trade-offs and the potential impacts on health. The consumer and their access to safe, nutritious, affordable, and aspirational food should remain at the core of our endeavors.

When considering the potential of alternative protein sources, we should reflect upon their contribution to dietary diversity. As availability and access to nutritious food is highly related to dietary diversity, this should not be an exception for alternative protein sources. The promotion of dietary diversity is vital to guarantee sustainable and nutritious diets as it is an indicator of diet quality. Issues related to dietary diversity accessibility are present in both the Global North (food desert, food swamps) and the Global South[12].

When discussing alternative protein products, we need to acknowledge the wide and varying needs for animal-sourced protein intake worldwide. In the Global North, it is recommended to moderate the intake of these foods as it has been found to be a risk factor for several diet-related diseases. In contrast, an increased intake of animal-sourced foods is generally advised in the Global South. In fact, animal-sourced products remain a great source of essential vitamins and minerals, and the consumption of these foods has been found to be significantly associated with reducing stunting[13]. Therefore, it emerged that the replacement of meat with alternative protein products is not always suitable for all global circumstances.

Furthermore, consumers should have access to nutritious food and be informed and guided by clear, realistic, and up-to-date food-based dietary guidelines. Consumers should be conscious of how to identify a healthy choice out of the countless possibilities and, in the context of alternative protein sources, should be aware of the fact that ‘vegan’, ‘vegetarian’, or ‘plant-based’ does not necessarily equal a ‘healthy’ option. Finally, the discussion around the nutritional impact of diverse proteins should be embedded within the broader debate on dietary diversity. There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution, and this discussion should be adapted to the local context and nutritional needs of different populations.

All graphics created by Sight and Life’s Architect and Design Specialist Anne Milan.

References

- FAO Burlingame B, Dernini S. Sustainable diets and biodiversity. 2010.

- Michel F, Hartmann C, Siegrist M. Consumers’ associations, perceptions and acceptance of meat and plant-based meat alternatives. Food Quality and Preference. 2020 Aug 20:104063.

- U.S Food & Drugs Administration, Daily Value on the New Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels. Accessed October 1, 2020. Online https://www.fda.gov/food/new-nutrition-facts-label/daily-value-new-nutrition-and- supplement-facts-labels

- WHO, Salt reduction fact sheet 2020. Accessed October 1, 2020. Online https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/salt-reduction

- Afshin A, Sur PJ, Fay KA, Cornaby L, Ferrara G, Salama JS, Mullany EC, Abate KH, Abbafati C, Abebe Z, Afarideh M. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2019 May 11;393(10184):1958-72.

- Curtain F, Grafenauer S. Plant-based meat substitutes in the flexitarian age: An audit of products on supermarket shelves. Nutrients. 2019 Nov;11(11):2603.

- Ekmekcioglu C, Wallner P, Kundi M, Weisz U, Haas W, Hutter HP. Red meat, diseases, and healthy alternatives: A critical review. Critical reviews in food science and nutrition. 2018 Jan 22;58(2):247-61.

- Craig WJ. Nutrition concerns and health effects of vegetarian diets. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2010 Dec;25(6):613-20.

- Monteiro CA, Cannon G, Lawrence M, Costa Louzada MD, Pereira Machado P. Ultra-processed foods, diet quality, and health using the NOVA classification system. Rome, FAO. 2019.

- Codex Alimentarius, FAO/WHO 2019 GSFA. Accessed October 1, 2020. Online http://www.fao.org/gsfaonline/additives/index.html

- Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, Garnett T, Tilman D, DeClerck F, Wood A, Jonell M. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. The Lancet. 2019 Feb 2;393(10170):447-92

- HLPE, Accessed October 1, 2020. Online http://www.fao.org/3/a-i7846e.pdf

- FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP and WHO. 2020. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2020. Transforming food systems for affordable healthy diets. Rome, FAO.

Read next

Discover more

News & announcements

Find out what is new at Sight and Life

Multimedia

Explore our videos, podcasts, and infographics