Plant-based meat and environmental sustainability: a complex story

Guest speakers: Dr Martin Bloem and Dr Adam Drewnowski

In this episode and blog, we explored the complex story around plant-based meat and environmental sustainability. It may have left us with more questions than answers, but this is the goal in our disruptive discussions and what science is all about!

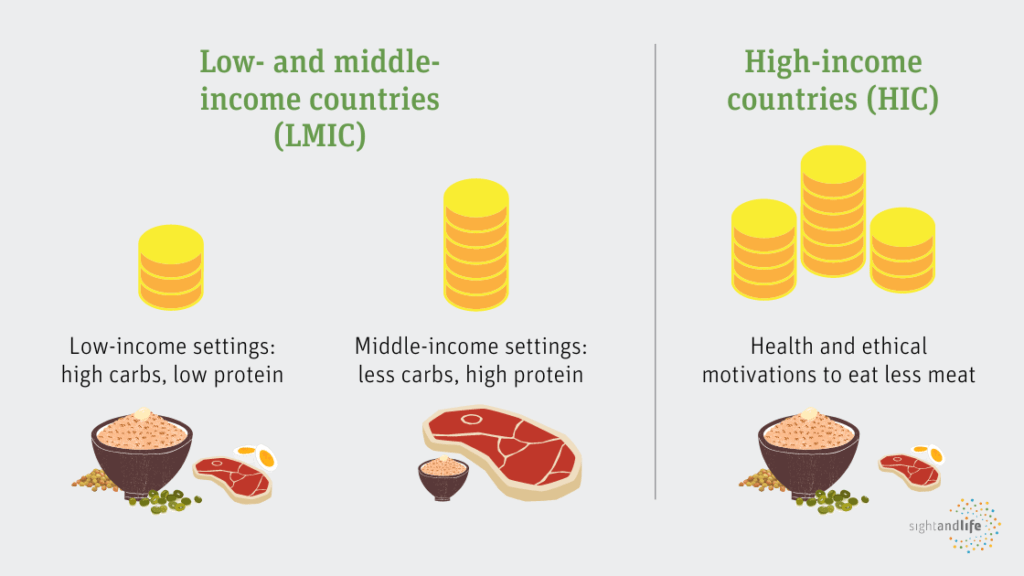

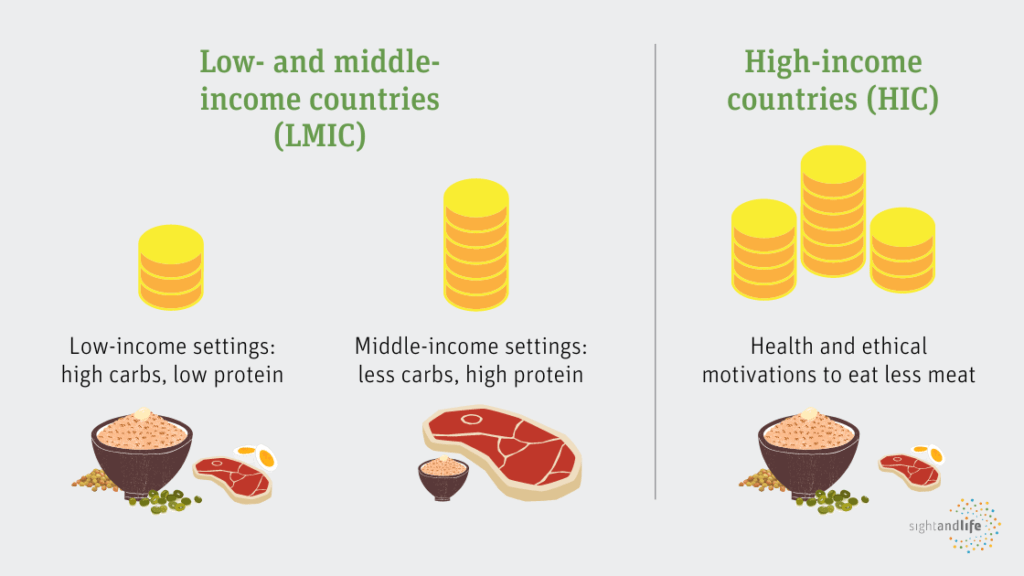

“The two opposing protein transitions”

Protein consumption differs in high- and low-income settings. Consumers in high-income countries (HIC) often have health and ethical (environmental impact, animal welfare) motives for reducing meat consumption, but also have a cultural attachment to the kinds of products that plant-based meats are imitating, such as hamburgers. In low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) however, consumption has often followed “Bennett’s law”: as incomes rise, people tend to swap out foods rich in carbohydrates but low in protein (e.g., rice), for foods denser in protein and other nutrients (e.g., animal products) (see Figure 1)(1). Dr Drewnowski refers to this phenomenon as the “two opposing protein transitions.”(1,2)

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the “Protein transitions in LMIC and HIC.”

If we apply this economic law to the two opposing protein transitions, Bennett’s law predicts an increased consumption of animal products following the growth of a country’s gross domestic product (GDP), unless consumers in LMIC are keener to incorporate alternative products into their diet. At this point in time, it is unclear whether plant-based burgers and similar products will be part of this transition, given that products like cow burgers have no history and limited appeal in many cultures outside the US, Europe, and Australasia.

Plant-based meat—the plant-based hamburger—is very much a niche product of interest to rich countries, but really has no interest to anybody else. Low- and middle-income countries never ate beef and may never get to eat beef because beef is at the apex of the nutrition transition.

Dr Drewnowski

Is plant-based meat good for the environment?

When it comes to the actual environmental impact of plant-based meats, the benefits remain a mystery. Available research suggests that traditional plant-based protein sources such as pulses and tofu are considerably less environmentally damaging than animal-based meats. It reveals that animal agriculture requires more land (hence contributing to deforestation), pollutes more water, and leads to more greenhouse gas (especially methane) emissions (3–10). However, plant-based meat is produced quite differently compared to the traditional plant and animal food categories. Much of the research which has been carried out has not been published in academic journals; it was pursued by private companies with specific agendas, or used questionable metrics to report environmental impact (11). Even so, plant-based meat is often touted to consumers as combining the desirability of animal-based meats with the sustainability of being plant-based.

Do environmental claims and marketing strategies affect consumer views on plant-based meat?

Market growth of plant-based meat alternatives is partly driven by consumer environmental consciousness(12). Companies such as Impossible Foods claim that their burger uses 87% less water and 96% less land, produces 89% lower greenhouse gas emissions, and reduces aquatic pollution by 92% compared to conventional ground beef(11). These claims sound very appealing to the environmentally conscious, but how reliable and trustworthy are these numbers?

Companies are beginning to report life cycle analysis of their products, which aims to account for all the above indicators. However, unclear claims have led to criticism, and even the banning of certain advertisements on the basis that they are misleading(13). And, as alluded to above, certain companies that do report the life cycle use a third party to calculate it, and the process is not peer reviewed or accessible to scientists nor consumers. Listen to this episode to hear more from Dr Drewnowski.

We are in a crisis. We have climate change, rising food insecurity, lowered incomes, which really means that we will have less choice about what to eat, meaning that we think we have a choice, but increasingly we have less and less choice and the choices are being imposed on us by powers beyond our control.

Dr Drewnowski

Can we trust the current environmental metrics?

Common metrics for assessing environmental impact measure one or more of the following indicators: water and land use, greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and pollution(14,15). We asked the experts about the best metrics for assessing the environmental impact of different products, and it appears that the jury is still out. We still do not have an agreed-upon best metric that takes into account the nutritional content of foods. Both experts agree however, that it would be suitable to start doing empirical research moving forward.

Most indicators of environmental impact are based on estimates of 1 kilogram of food(14,15), but this is likely not the best way to compare different food choices, as the kilogram does not consider the food’s nutrient density. In this episode, Dr Drewnowski thoughtfully takes us through this consideration and his work on the topic(16,17). He also mentioned the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO)’s conclusion that 1 kilogram was not a good measure of nutrition, because the function of the food is to provide calories and nutrients, which over recent decades do not typically correlate with the weight of food.

A nutrition-related functional unit which considers the environmental cost per nutrient is needed for a relevant life cycle analysis and to effectively draw conclusions about environmental impact. A key consideration here is that plant and animal proteins come with a variety of nutrients, while manufactured proteins carry few nutrients(16,18). This is because of the manufacturing and processing methods mentioned in the Episode 1 blog of this series.

The EAT-Lancet Diet: an environmentally friendly diet (for some countries)

The EAT-Lancet Diet, or Planetary Health Diet developed by the EAT-Lancet commission(19), provides a framework for healthy eating for both planet and human health. This reference diet suggests daily consumption ranges for each food group that are science-based and flexible to honor local and cultural considerations(19,20). For example, proteins should consist of approximately 15% of a person’s energy intake per day and available protein sources are wide-ranging; animal-sourced proteins are still allowed, but at lower quantities than plant-sourced proteins(19). Contrary to common expectations, plant-based meats are not included in the EAT-Lancet Diet. We asked the experts to shed light on why diverse proteins, specifically plant-based meats, weren’t considered in this diet and whether they should be included.

The distinction is between (the following sources): plant proteins – no problem;

diverse proteins as ingredients in foods – no problem;

and the plant-based burger, a niche product of interest to people in the US and not to anybody else globally – no.Dr Drewnowski

The bleak reality for many LMIC when it comes to the EAT-Lancet diet is that although adopting it would result in less malnutrition, it would actually lead to more animal-sourced protein consumption, GHG emissions, and cost. Dr Bloem and colleagues confirm this in a study which looked at the environmental impact of the Planetary Health Diet in Indonesia(20). The current diet of Indonesians is less diverse and higher in grains and starchy roots than those modeled in the Planetary Health diet, which often leads to nutrient deficiencies and malnutrition(20). Therefore, alternatives to animal-sourced protein, that are environmentally, nutritionally, economically, and culturally viable are needed for these countries with growing economies to mitigate the effects of climate change and malnutrition.

Looking ahead: research, frameworks, and policies

Plant-based meat alternatives present an opportunity for environmentally friendly and sustainable diets. There are still gaps however, in assessing their actual impact in the long term. That is why we need more investment and improved research on diverse proteins and plant-based meat products to determine their consumption’s environmental and health impacts. Building the data and advancing our knowledge in these areas will be essential to ensure we are truly working toward better planetary and human health with these alternatives.

There are research and data gaps regarding metrics, including sustainability of proteins, which has four domains: health, economics, environment and society.

Dr Drewnowski

Dr Bloem underscored the need for continued research too, but also highlighted the importance of not waiting for data and for products to be “perfect” to implement action because we need alternative solutions now. Listen to the episode to hear what policies, regulations and frameworks Dr Bloem thinks are needed.

It’s important to know what is actually needed and based on that, you have to also adjust your agriculture and look into what’s possible at the country and global level.

Dr Bloem

Bringing it all together

There is an urgent call for governments, food system actors and academia to develop sustainable, nutritious, and safe food; this is especially important in LMIC, where protein consumption is still low and dietary patterns are changing, according to the two opposing protein transitions.

Instead of thinking what plant-based meats offer now, all actors should have long-term thinking and programming – that’s critical.

Dr Bloem

New and sophisticated food technologies and ingredients are being used. However, these seem far from the infrastructure and capacity reality in LMIC(21). On the other hand, ancient methods such as “fermentation” –which is more affordable and culturally accepted across different regions– are being used to produce sustainable and nutritious plant-based alternatives.

A common criticism of plant-based meats is that they require processing, but even though processing can strip away natural nutrients like vitamins and minerals, in some cases, it can improve the protein quality and digestibility of plant-based proteins(18). With product reformulations, we could see a future of products with fewer unwanted, harmful added ingredients such as sugar, saturated fats and salt, and more desired ingredients such as the micronutrients, fiber, and plant protein isolates to improve nutrient profiles(16). Plant-based meat products with better nutritional profiles have the potential to reduce impact on the planet(18) by lowering the need for animal-based agriculture(10,18).

In summary, plant-based meat holds promise for future protein-source alternatives. However, research and development to increase their nutrient density and assess environmental sustainability are still at the “novice stage”. Without investment and rigorous research into their total effects on human and planetary health, we are left with many unanswered questions. More data will be needed to unveil how plant-based meat and similar products could be a nutritious, sustainable, and affordable solution that is culturally accepted worldwide.

We were pleased to learn more about this topic with the help of two experts: Dr Adam Drewnowski, Director of the Center for Public Health Nutrition and Professor of Epidemiology at the School of Public Health, University of Washington; and Dr Martin Bloem, Director of the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering, at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. We also were pleased to co-interview with Dr Simon Brown, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University and member of the Alternative Protein Project chapter.

We need to embrace complexity and use different angles to look at impact. If we don’t start to do this kind of research and discussion at different levels, we can lose the battle.

Dr Bloem

If you are interested in being part of the solution towards a more sustainable Food System, enroll in a course developed by Harvard Business School and Sight and Life on Food Systems Live! – Entrepreneurship in Emerging Economies.

References:

- Drewnowski A, Poulain JP. What Lies Behind the Transition From Plant-Based to Animal Protein? AMA J Ethics. 2018 Oct 1;20(10):E987-993.

- Drewnowski A, Mognard E, Gupta S, Ismail MN, Karim NA, Tibère L, et al. Socio-cultural and economic drivers of plant and animal protein consumption in Malaysia: the SCRiPT study. Nutrients. 2020;12(5):1530.

- A Global Assessment of the Water Footprint of Farm Animal Products | SpringerLink [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 7]. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10021-011-9517-8

- Alexander P, Brown C, Arneth A, Dias C, Finnigan J, Moran D, et al. Could consumption of insects, cultured meat or imitation meat reduce global agricultural land use? Global Food Security. 2017;15:22–32.

- Hayek M. Missing the grassland for the cows: Scaling grass-finished beef production entails tradeoffs—Comment on “Grazed perennial grasslands can match current beef production while contributing to climate mitigation and adaptation”. Agricultural & Environmental Letters. 2022;7(2):e20073.

- Hayek MN, Harwatt H, Ripple WJ, Mueller ND. The carbon opportunity cost of animal-sourced food production on land. Nat Sustain. 2021 Jan;4(1):21–4.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Special Report on Climate Change and Land [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 7]. Available from: https://www.ipcc.ch/srccl/download/

- Searchinger TD, Wirsenius S, Beringer T, Dumas P. Assessing the efficiency of changes in land use for mitigating climate change. Nature. 2018 Dec;564(7735):249–53.

- Poore J, Nemecek T. Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers. Science. 2018 Jun;360(6392):987–92.

- Scarborough P, Appleby PN, Mizdrak A, Briggs ADM, Travis RC, Bradbury KE, et al. Dietary greenhouse gas emissions of meat-eaters, fish-eaters, vegetarians and vegans in the UK. Climatic Change. 2014 Jul 1;125(2):179–92.

- Impossible Burger Environmental Life Cycle Assessment 2019 [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 7]. Available from: https://impossiblefoods.com/sustainable-food/burger-life-cycle-assessment-2019

- Sanchez-Sabate R, Sabaté J. Consumer Attitudes Towards Environmental Concerns of Meat Consumption: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019 Jan;16(7):1220.

- Tesco plant-based food advert banned as misleading. BBC News [Internet]. 2022 Jun 8 [cited 2022 Sep 9]; Available from: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-61731187

- de Pee S, Hardinsyah R, Jalal F, Kim BF, Semba RD, Deptford A, et al. Balancing a sustained pursuit of nutrition, health, affordability and climate goals: exploring the case of Indonesia. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021 Nov 8;114(5):1686–97.

- Kim BF, Santo RE, Scatterday AP, Fry JP, Synk CM, Cebron SR, et al. Country-specific dietary shifts to mitigate climate and water crises. Global Environmental Change. 2020 May 1;62:101926.

- Drewnowski A, Detzel P, Klassen-Wigger P. Perspective: Achieving Sustainable Healthy Diets Through Formulation and Processing of Foods. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2022 Jun 1;6(6):nzac089.

- Drewnowski A, Smith J, Fulgoni VL. The New Hybrid Nutrient Density Score NRFh 4:3:3 Tested in Relation to Affordable Nutrient Density and Healthy Eating Index 2015: Analyses of NHANES Data 2013-16. Nutrients. 2021 May 20;13(5):1734.

- Kennedy ET, Buttriss JL, Bureau-Franz I, Wigger PK, Drewnowski A. Future of food: Innovating towards sustainable healthy diets – Kennedy – 2021 – Nutrition Bulletin – Wiley Online Library [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 9]. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/nbu.12523

- Willett W, Rockström J, Loken B, Springmann M, Lang T, Vermeulen S, et al. Food in the Anthropocene: the EAT-Lancet Commission on healthy diets from sustainable food systems. Lancet. 2019 Feb 2;393(10170):447–92.

- Semba R, Ramsing R, Rahman N, Bloem M. Providing planetary health diet meals to low-income families in Baltimore City during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development. 2020 Oct 19;10(1):205–13.

- Chapter: New food sources and food production systems [Internet]. [cited 2022 Sep 16]. Available from: https://www.fao.org/3/cb8667en/online/src/html/new-food-sources-and-food-production-systems.html

Read next

Discover more

News & announcements

Find out what is new at Sight and Life

Multimedia

Explore our videos, podcasts, and infographics